There’s been a shift in the way large technology companies structure their technical teams and architecture. Traditionally, engineering teams have been organised together in large working groups and the code they produce layered on top of each other. Today, however, many large technology companies are reorganising their architecture – and their teams – into more efficient models.

This new design pattern, known as microservices, has been a hot topic of conversation among CTOs, technical directors, architects, and leaders of technical teams. Everyone is in agreement that the microservices design is the most efficient and effective way to approach large-scale technical projects. However, few can agree on the exact way of structuring their microservices.

Technical Director Matt Meckes recently participated in a roundtable discussion on this very topic. Specifically, Matt discussed the benefits of microservices, the implementation challenges many teams face, as well as the companies that can most benefit from this new design pattern. We caught up with Matt after his talk to learn more about microservices.

Microservices and Their Unique Approach to Scalability

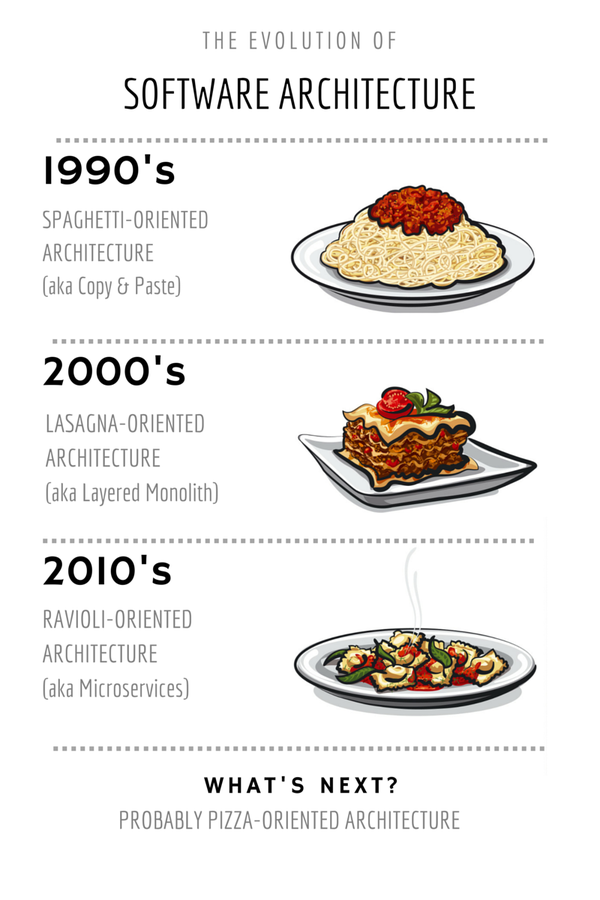

The best way to describe microservices is to think of it like food. In the 1990’s, code was organized like spaghetti and everything was a big jumble. Over the next decade, the structure was improved and code was designed in layers like lasagna. Today, a new iteration has created ravioli architecture, which is a bundle of everything wrapped in self-contained blobs.

“That’s the general idea of microservices,” Matt says. “Instead of having a great big database as the bottom layer with a logic layer and a UI layer on top, microservices actually splits small pieces of business logic, functionality, and data into self-contained little units.”

The benefit of this microservice-type architecture is all about scalability. Matt explains further by saying that, “Microservices were first popularised by Amazon, and the idea is that if you’re doing lasagna architecture, as the whole project grows, each of the teams gets bigger and bigger, causing you to spend more time managing the team than delivering the code.

“Amazon addressed this problem with what’s called ‘pizza box teams’. Basically, the company organised itself into multiple self-sufficient tech teams that work on a small piece of a larger project. Each team is full-service, meaning that there are UI developers, testers, back-end engineers, and more. Further, each team is small enough that it can be fed by two large pizzas.”

This organisation helps companies like Amazon scale their overall engineering efforts quickly and keep their teams agile and adaptable to change. And the benefits of microservice scalability don’t stop there. In fact, it’s only the beginning.

“Scalability of server architecture is also a huge benefit of microservices,” Matt says. “If you build a monolithic type of application, for example, you have to run it on 3 or 4 servers – with each one a layer. However, as you scale, you’ll need to make these servers increasingly larger until you reach the limit of the largest server possible, causing issues.

“With microservices, you can break up a single process into thousands of little pieces and put each one of those microtransactions on a server. It’s possible to have 10s or even 100s of those little pieces running on a single server. As you grow your application over time you can scale much more efficiently. This, of course, will also reduce your costs.”

Because of all of these scalability benefits, microservices has become very popular. However, since this design pattern is so new, there are a lot of challenges that come along with it. There is currently little consensus around design patterns, and people are quick to debate the best ways to move from monolithic architecture to microservices.

Challenges of Building a Team Using Microservices

Creating microservices is easy when you’re building individual services with limited functionality, such as applying a discount code or filling out a registration page. Where it starts to get really complicated is when you have to coordinate the way in which each of these standalone units work together.

“You can imagine someone trying to register for a service like Netflix,” Matt explains. “There are a lot of steps in that process and they all need to happen in a particular order. Some of these steps are important while others aren’t. For example, if a payment doesn’t get processed the registration should stop. But if Netflix can’t pull a profile picture from Facebook, the registration should probably continue.”

This example makes it clear that the coordination of each microservice is essential if the overall process is expected to work. Currently, there are two approaches to the microservice design pattern. The first approach came about early in the timeline of microservices, known as orchestration.

“With orchestration, you have a conductor in the middle who’s telling everyone what’s happening next,” Matt tells us. “This helps simplify the mental model but it gives you a single point of failure, and in effect creating a new form of modular monolith.”

The other approach is a newer one that seeks to solve the problem of the single point of failure. Known as choreography, this approach has been pioneered by architects Martin Fowler and James Lewis, who warn that if the component microservices aren’t composed cleanly and with self-sufficiency, the connection between them will weaken and break.

“Choreography is where every individual microservice does its own thing with no top-down control,” Matt says. “All of the microservices self-organise into some sort of dance, where even if some of them get the steps wrong, there is no single point of failure and the overall process can continue without more than a hiccup. The challenge is that without consensus around tooling and design patterns, you need to create the logic to choreograph services from first principles. Fine if you are Amazon and can hire comp-sci Phds on each of your service teams, but not yet practical for the masses.”

How to Approach the Implementation of Microservices

The major issue with microservices isn’t a tech problem but is rather a people problem. When asked what Matt thought was the best approach for microservices implementation, he said that the initial steps shouldn’t involve the architecture at all. Instead, it should focus on the people within each microservice team.

“I actually think that it’s the human element that’s most important,” Matt says. “A lot of people lose sight of that. If you have thousands of engineers and you’re trying to manage scale, it’s better to create 1,000 departments with 10 people rather than 10 departments with 1,000 people. This team organisation is the first step and is the most important.

“Out of that initial organisation comes a design pattern that reflects natural architecture. That’s where microservices has a huge benefit. The human organisation will help dictate the organization of the code. When we help our clients transition from a traditional monolithic structure, the effort isn’t reorganising the technical architecture. Instead, it’s all about meeting the people and dividing them up into the right groups.”

However, Matt stresses that it’s important to think of microservices in terms of a hype curve. For those unfamiliar with a hype curve, it plots the visibility of the technology process over time. Currently, microservices is reaching a high point on the hype curve known as the “peak of inflated expectations.”

This peak measures the fact that everyone is excited about something new like microservices, and even though it might be beneficial, too many people think it can benefit them. This means that too many companies believe microservices is the answer, when in reality, it still might not be suitable for their company.

“We all agree that if you’re the size of Amazon,” Matt says, “then microservices is a great architecture to implement. However, if you’re not at the scale of an Amazon or a Netflix, for example, it’s probably best to hold off on microservices. A lot of companies with 10 or fewer developers want to implement microservices, but if you can feed your entire team with just a few pizza boxes, microservices probably isn’t necessary.”

Matt went on to say that “The more traditional monolithic design pattern is still better for companies with small technical projects. Microservices is great for building a skyscraper, but if you’re building a small cabin in the woods than microservices probably isn’t applicable to you or your business. However much like technology from a formula 1 team eventually drip feeding down into production cars, patterns used in Microservices are informing development across the whole industry giving us many of the benefits, without all of the overhead.”

Still, even with the over-hype, experts expect microservices to get increasingly better and more refined. Currently, there are not a lot of best practices regarding microservices. Soon, however, the hype will go away and what will remain is a widely-usable design pattern that benefits the technology industry as a whole.

Conclusion

Overall, if you have an engineering team that numbers in the hundreds or thousands, then microservices is a good option for your architecture. If you have a smaller team, however, then it’s probably best to stick to the traditional monolithic layered architecture.

While microservices sounds exciting (and it is), the worst thing you can do is unnecessarily restructure your team and your code. Instead, stick with what works until you expect to scale into the hundreds of millions of users.

However it is equally important to see where new techniques such as containerisation, and improved patterns for encapsulation can improve your product, even if you still have a shared database layer behind it all.